Find A Host Page, No Filters Applied

When WWOOFers begin to navigate the WWOOFusa site, the first stop after creating a worker profile is often the “Find A Host” page. The site currently has almost 1,500 different available farmstay options located in all 50 states in urban, suburban, rural, and remote locations. To find a location that meets a WWOOFer’s specific needs, the site provides several filtering options.

Filter Options

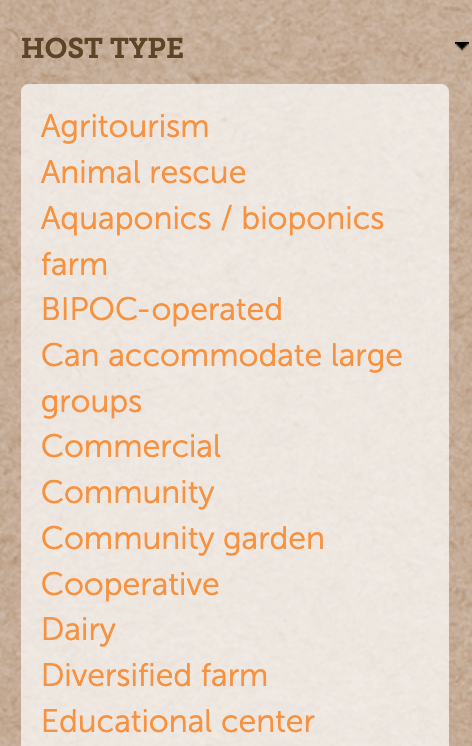

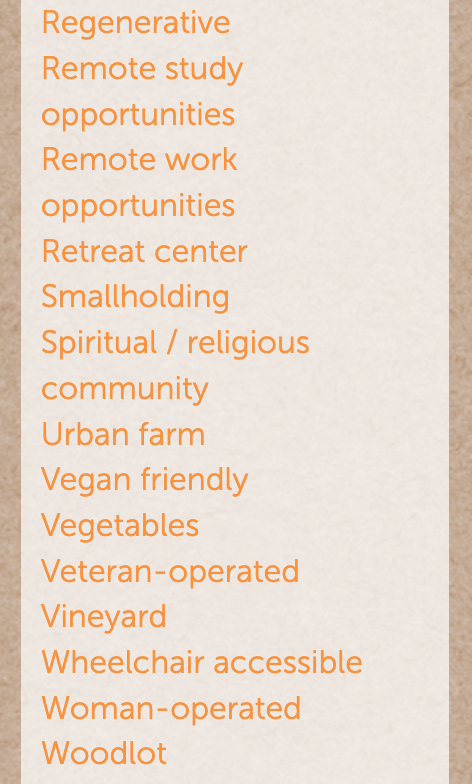

The filters offered by the WWOOFusa site allow farmstays to describe their opportunities in great detail. Hosts are responsible for labeling their locations correctly and specifically and can provide detailed information on their farm pages. WWOOFers can sort by availability, relevance, or new host(how recently the host joined the WWOOFusa program). Farmstays can be listed as being “immediately available,” “open now,” “open next season,” or “closed” depending on their farm’s current needs. The filter options I am most concerned with in regards to this project are those listed under “Host Type”. There are forty different Host Types, and hosts can select as many as they need to appropriately describe their farmstay opportunity.

On Host Type Filtering

-

The three images above display the forty “Host Type” listings available as filtering options. When I chose to go WWOOFing, I was most interested in working at a Homestead that revolved around goats. I also wanted to find a farm that employed permaculture techniques in their methodology that wasn’t too far from my home, in case the stay didn’t work out as well as I’d hoped. I was interested in working at a BIPOC and/or LGBTQ-operated farm, but there were no BIPOC-operated farmstays that met my other needs that were within a feasible driving distance. The farm I stayed at was LGBTQ-operated and LGBTQ-friendly, but most of the people I worked and interacted with were white.

-

As far as I can tell, there are no clear definitions of how WWOOFusa defines BIPOC, nor any way to determine the truthfulness of hosts who elect to use this filter on their host page. This poses a problem because there are two contradicting definitions of the term: Black, Indigenous, People of Color vs Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. As stated by the BIPOC project, which ascribes to the first definition, the term is used “to highlight the unique relationship to whiteness that Indigenous and Black (African Americans) people have”. By highlighting this relationship to whiteness as distinct from that of non-Black and non-Indigenous POC’s, it calls attention to the way white supremacy pits various minorities against one another in a manner that reaffirms a gradiated racial hierarchy. The second definition, which includes all POC but emphasizes Black and Indigenous POC, does highlight the realities of being Black or Indigenous as distinct from other POC groups, but still allows non-Black and non-Indigenous POC to group themselves under the term. How many of the farmstays that advertise themselves as BIPOC-operated fall under the second definition and not the first?

Of the nearly 1,500 farmstays listed on WWOOFusa, only 3.8% are listed as BIPOC-operated. While some farmstays may be BIPOC-operated and simply haven’t listed themselves as such, this is still an incredibly small number, especially considering that there are thousands of Black and/or Indigenous-operated farms, community gardens, homesteads, or other kinds of food-growing operations currently functioning in the US. What factors prevent these farm sites from utilizing WWOOFusa, and are there ways for WWOOF to better serve these farmers?

When young people who are interested in farming begin to seek out work opportunities and educational resources, WWOOF is one of the most popular non-collegiate resources that folks use to get involved. If they, like me, are interested in learning from BIPOC farmers but are determined to not let their membership fee go to waste, they might come to the false conclusion that learning about sustainable and sustaining farming techniques from BIPOC farmers is difficult if not impossible. While WWOOFusa is not necessarily obligated to list the thousands of farm operations that aren’t affiliated with them, the scarcity of BIPOC-operated hosts available creates an illusion that BIPOC farming operations are not really present in the US. Intentional or not, this disparity contributes to the idea that Black and Indigenous communities across the country are not interested in creating sustainable, self-reliant food systems, and that ecologically conscious agriculture is a white invention.

On the other hand, nearly half of the farmstays listed on WWOOFusa claim to employ some form of permaculture in their farming practice. For more information on what exactly permaculture means, refer to the permaculture keyword essay. There are countless ways to employ permacultural techniques in a farm environment, and no easy way to define what permaculture should look like. But, crucially, while many of the farming methodologies employed by Black and Indigenous farmers are rooted in permacultural techniques (and are even the sources for the creation of the term by white food scholars in the 1970’s), because of the term’s history and Western-influenced focus on productivity, it does not accurately capture the methodologies and philosophies invented, modified, and employed by Black and Indigenous farmers, who often prefer to use more culturally-relevant and specific terms to describe their farming approaches. However, these terms are not necessarily offered as Host Type or Methodology filters, and Black and Indigenous farmers may not be familiar with the ways their farming approaches use permacultural techniques.

Of the farmstays that label themselves as BIPOC-operated, about half also understand their farming approach as one that uses a permacultural farming approach. While we can’t say for certain that the other farmstays do or don’t use farming methodologies that could be recognized as permaculture, WWOOFers who are interested in learning about permanent agricultural techniques are likely further discouraged from learning from the Black and Indigenous farmers who haven’t listed their Host Type as permacultural, regardless of the sustainability and ecologically conscious farming methods they might employ.

There is no way for BIPOC farmstay hosts to describe their sustainable farming methodologies outside of permaculture in a way that is easily searchable on the WWOOFusa website. While they can further explain their styles of work on their host description page, for young WWOOFers who aren’t yet familiar with the many kinds of sustainable farming practices inside and outside of Black and Indigenous-led farm work, nearly half of the few BIPOC-operated opportunities available to them might be easily written off because they don’t use the word permaculture to describe their work. Despite the ecological consciousness present in the work of most BIPOC farmers, their farmstays are quickly omitted from the realm of host possibility should they choose to omit permaculture as a filtering option.

As a young white person who only somewhat recently became interested in exploring sustainable agriculture techniques, one of the first terms I heard was permaculture. Even though I didn’t fully begin to understand what the term meant until I’d been involved in the farming world for a few months, I recognized it as a signifier of a more ethical and ecologically conscious farming approach from the beginning. It was only after learning more fully about what permaculture means and doing research on Black and Indigenous farming practices that I began to understand how traditional Black and Indigenous agrarian methodologies employ sustainable relationships with the earth in ways that include and go beyond the realms of permaculture.

How, then, do we rectify the lack of possibility imagined by the WWOOFing maps? How do these maps hinder young farmers from learning about caring for this land from the original land stewards? In what ways are BIPOC-led farming and food sovereignty operations creating food futures that are not legible through the WWOOFusa program? How can we map this refusal of the nothingness and passivity narrative that the WWOOFusa maps further?